Blog

How Attackers Run Smishing Campaigns (And Why They Work)

By Daniel Kelley, Threat Researcher

Feb 4, 2026

Smishing (short for SMS phishing) refers to fraudulent text messages sent by attackers to trick victims into revealing sensitive information or installing malware.

In recent years smishing has exploded as a top mobile threat vector, with an estimated 300,000–400,000 scam texts being blasted out every single day. These fake SMS alerts impersonate banks, delivery services, government agencies, and more, luring recipients with urgent problems or enticing offers. With the average cost of a successful smishing attack exceeding $9.5 million per organization, it's a business risk that security teams can't afford to overlook.

This post will walk through how smishing campaigns are built, from gathering huge lists of phone numbers, to choosing the infrastructure for sending out messages, to the final payload that unwitting victims see on their phones. We'll peel back the curtain on the real-world tactics so you can better defend against them.

Acquiring Bulk Campaign Target Data

For cybercriminals, the first step in a smishing campaign is obtaining targets - i.e. massive lists of phone numbers (often with associated names or other details). Unlike email phishing where addresses are abundant, mobile numbers are a bit more guarded. Yet, attackers have several avenues to source tens of thousands or even millions of victim phone numbers. Three common methods include:

Buying from Data Brokers (IAB-Based Lists)

A thriving data broker industry trades in personal contact data for marketing, and cybercriminals take full advantage of this. These brokers collect phone numbers from many sources: public records, mobile apps, online tracking scripts, and commercial partnerships. This includes phone numbers that consumers willingly provide to retailers and ecommerce sites in exchange for discounts or promotional offers. Often, the data is categorized by demographics or interests, meaning a buyer can request targeted lists (e.g., "mobile numbers of banking customers in Florida" or "users interested in crypto investing").

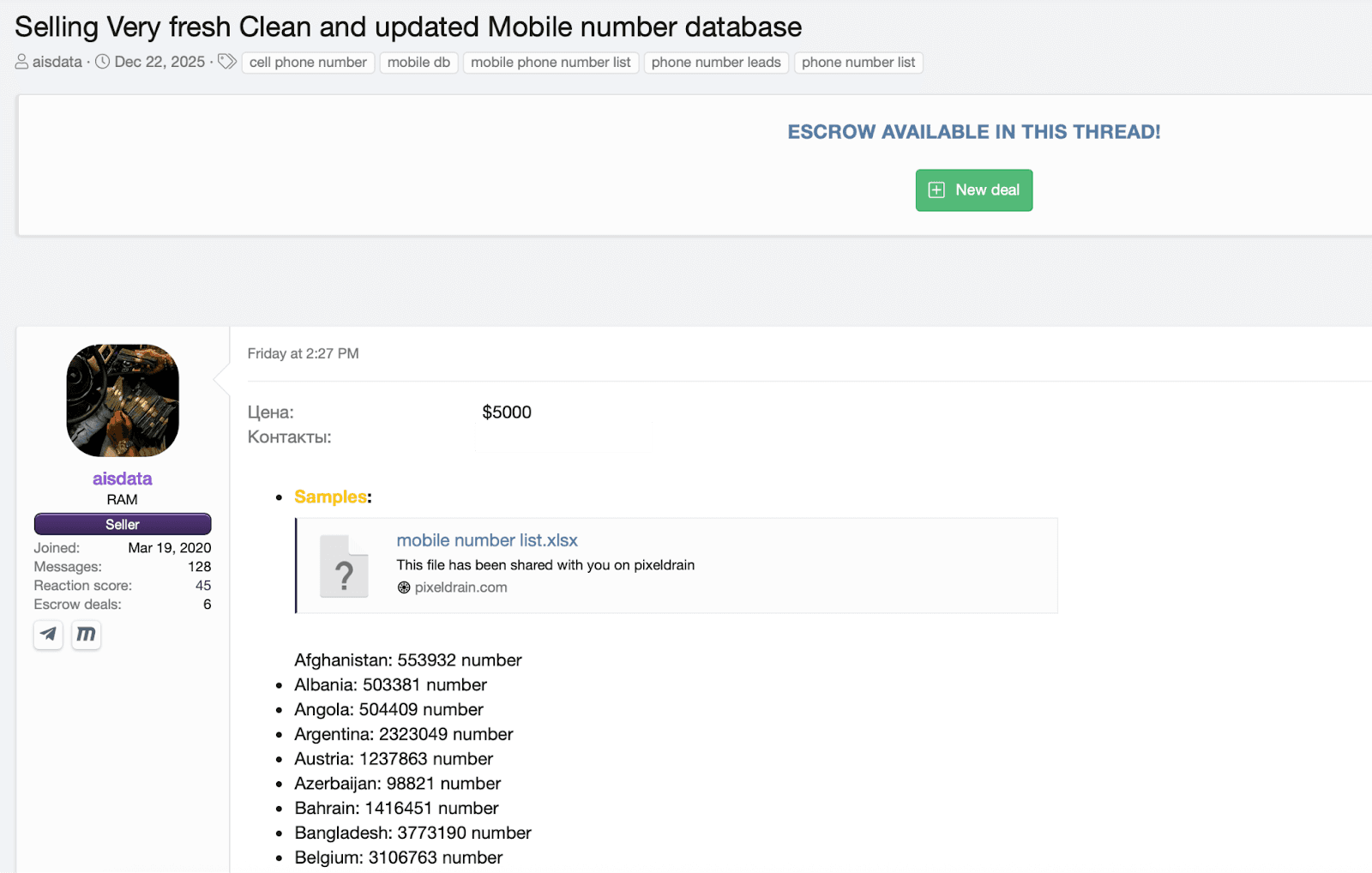

Figure 1: A dark web post selling “fresh” mobile number databases.

Data brokers don’t vet their customers. Attackers can anonymously purchase bulk phone number lists for a few dollars with just a click. There’s little to stop a malicious actor from buying, say, 100,000 phone contacts filtered by specific region or age group.

Hacked and Leaked Databases (Darknet Sources)

The next method is hacked and leaked databases. The underground economy is flooded with stolen user databases from breaches, and many include phone numbers. When online services are breached or hacked, the leaked records (which often contain names, emails, phone numbers, etc.) get traded on dark web forums. Smishing crews scour these breach dumps or buy them outright. A breach of a large service or telecom provider might expose millions of mobile numbers at once.

Figure 2: A Marketplace listing offering enriched contact data for targeting.

Threat actors openly advertise such data. If a company you use loses your data, your number could end up in a cybercriminals address book the next day. Attackers also obtain phone contacts by purchasing credential combo-lists or marketing leads on darknet marketplaces, then use those for broad smishing campaigns.

Cloud Misconfigurations & Exposed Backups

Not all data leaks come from traditional hacks, a lot of phone data gets spilled through IT mistakes. Companies sometimes leave databases or storage buckets unsecured in the cloud, effectively publishing their customer contact lists to the internet. Cybercriminals actively hunt for these misconfigurations. When such a trove is found, criminals waste no time harvesting it.

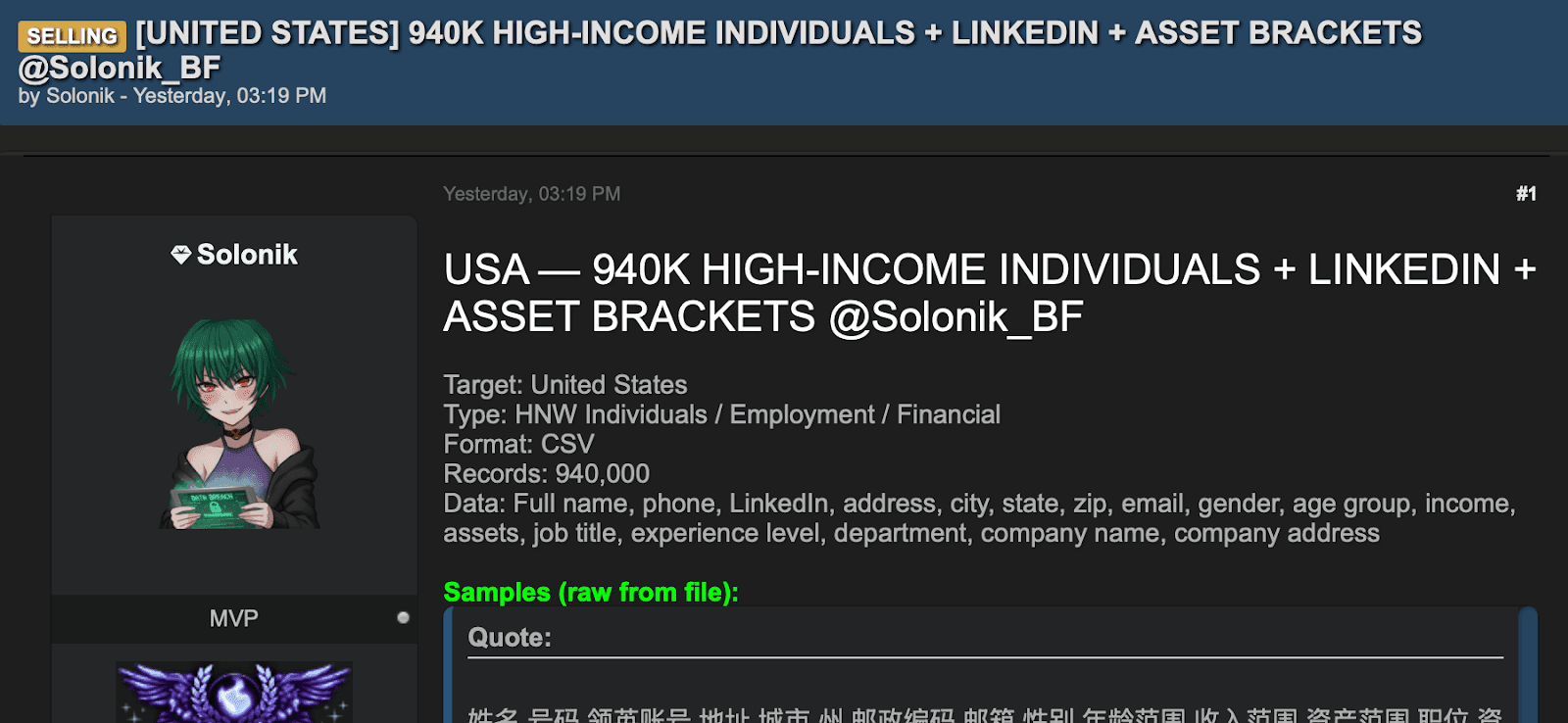

Figure 3: A tool used to find exposed cloud storage leaking datasets.

Misconfigured cloud backups or databases (e.g. open Elasticsearch indexes, Firebase databases, etc.) have revealed millions of contact details. Attackers exploit these leaks by downloading the phone number lists and then rolling them into their smishing target sets. This method is essentially “free” data, the attackers didn’t have to pay for the information or breach a system; they simply found treasure left out in the open due to poor security hygiene.

Choosing Infrastructure for Sending Smishing Messages

Armed with a list of targets, the attacker’s next challenge is how to actually deliver thousands of SMS messages, preferably without being shut down immediately. Unlike email, sending SMS at scale typically requires access to telecom infrastructure or specialist services. Cybercriminals have developed several ways to blast out smishing texts while masking their tracks. Common tactics for the sending infrastructure include:

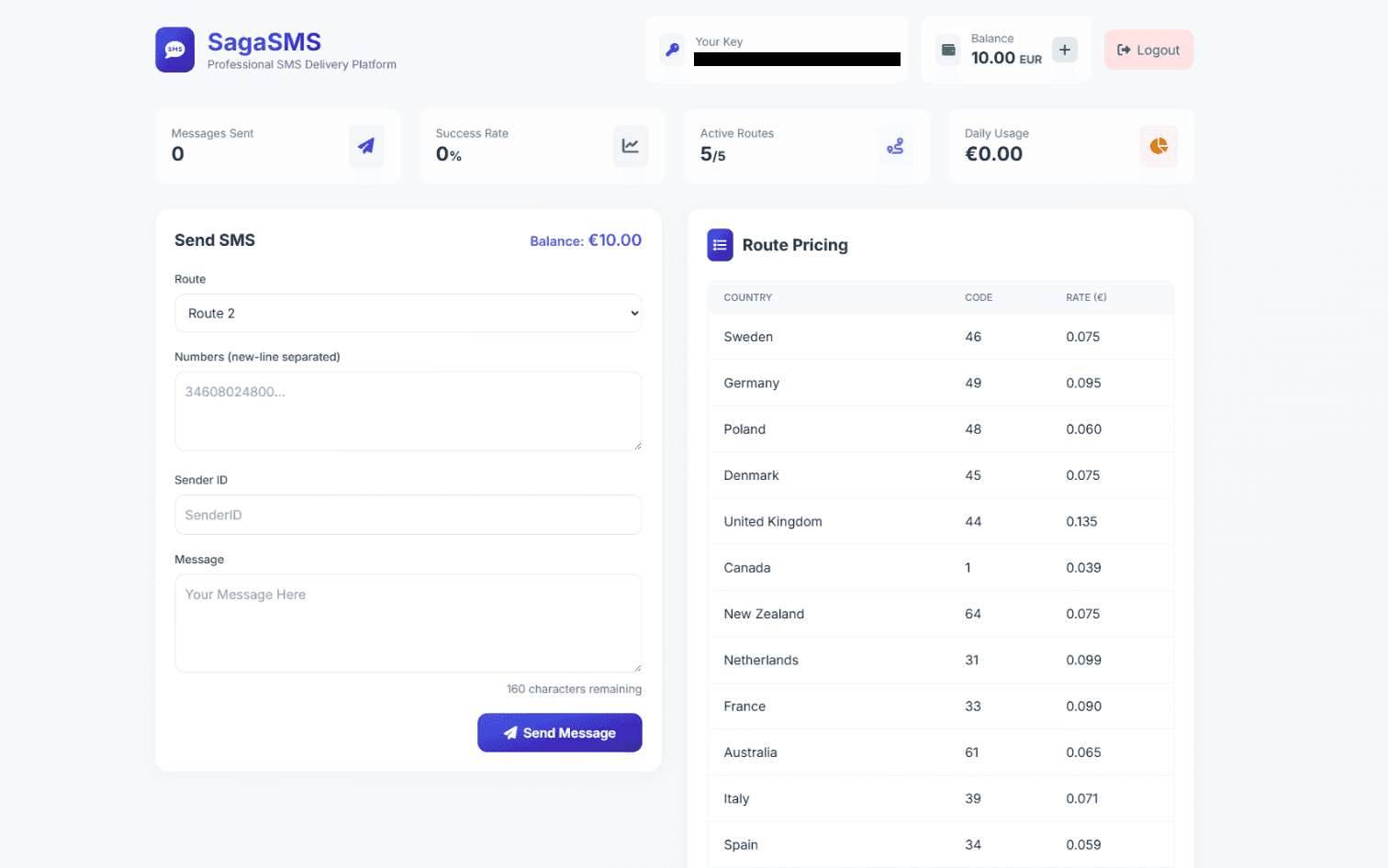

Bulk SMS Gateways and Messaging Services

Many cybercriminals piggyback on the same bulk messaging platforms used by legitimate businesses. Services like SMS gateways, online texting APIs, or telecom cloud providers (think Twilio, Nexmo/Vonage, Plivo, etc.) allow users to send messages in bulk for fractions of a penny per text. Attackers obtain accounts on these platforms, sometimes using fake/stolen identities and payment, or by hijacking someone else’s account, and then deploy their phishing SMS en masse. Cybercriminals can send tens of thousands of SMS phishing messages for as little as $0.005 per message using low-cost SMS gateway services.

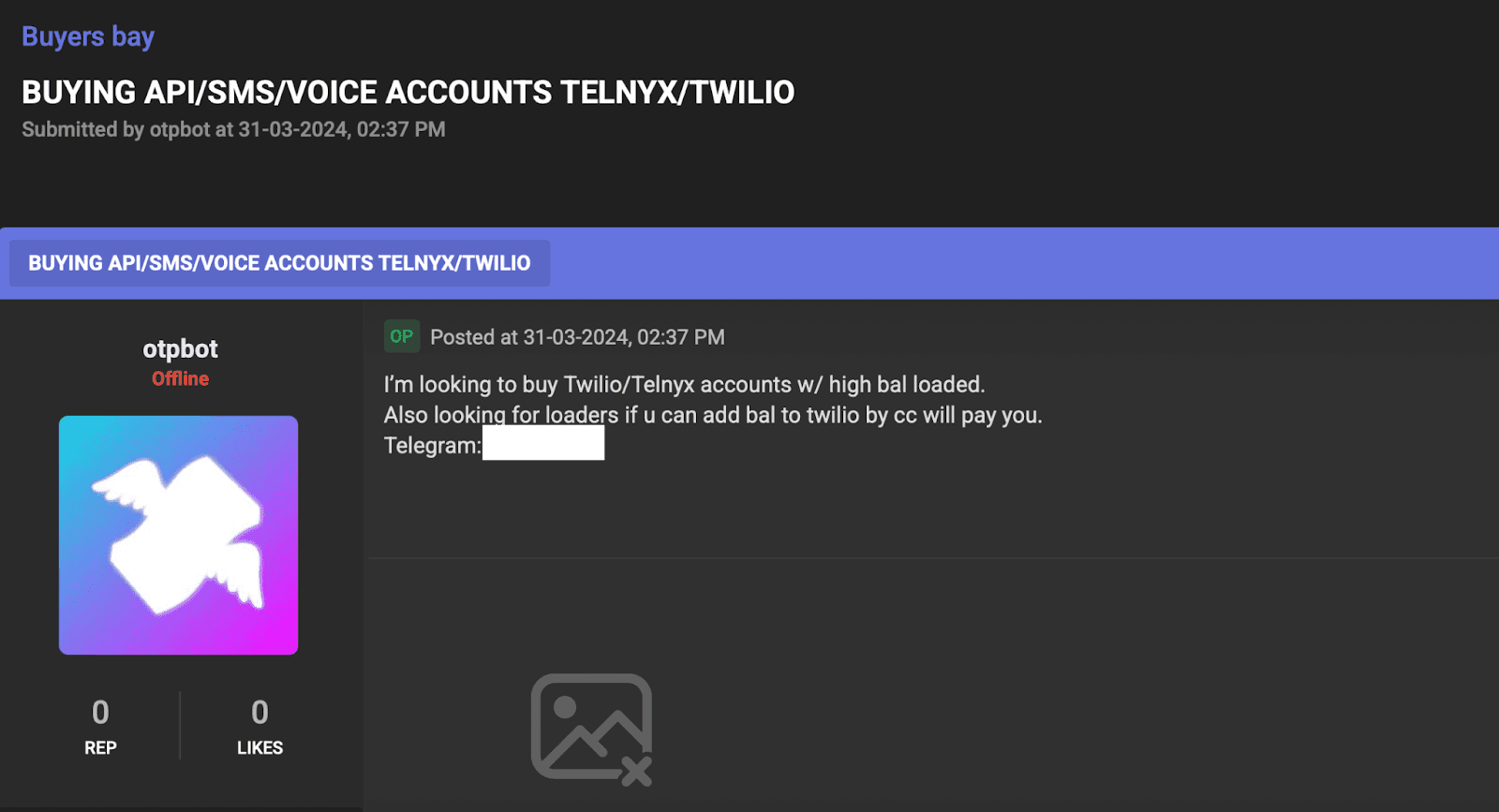

Figure 4: A cybercriminal looking for Twilio/Telnyx SMS accounts for bulk smishing.

This ultimately means an attacker could blast out 100k texts for only a few hundred dollars. Bulk SMS providers do have anti-abuse measures, but skilled attackers may rotate through multiple services or use smaller providers that have lax enforcement. By leveraging commercial SMS delivery channels, attackers get high deliverability (messages go through legitimate telecom routes) while keeping costs low, a potent combination that fuels large campaigns.

SMS Spoofing Tools and Sender ID Tricks

Part of the smishing infrastructure is also the software used to customize message origins. Attackers use SMS-sending tools (including underground SMS spam kits and even phishing-as-a-service offerings) that let them spoof the sender ID. This means the text can appear to come from a trusted name or number rather than the attacker’s device. Many bulk SMS systems and SIM gateways allow the sender to be an alphanumeric string (e.g. a company name) or a phone number of the attacker’s choosing. Attackers exploit this to make messages look like they’re from “BankOfAmerica” (for example) or a local number in the victim’s area code.

Figure 5: A SMS spoofing panel used to impersonate trusted senders.

Fake texts are easier to execute with sender spoofing, cybercriminals can simply supply a false sender name when routing through certain networks. There are kits for sale that automate this process, some even including templates and management of replies. Essentially, today’s smishing toolkits make it point-and-click simple to customize the “from” field, bypassing the origin authentication that SMS sadly lacks.

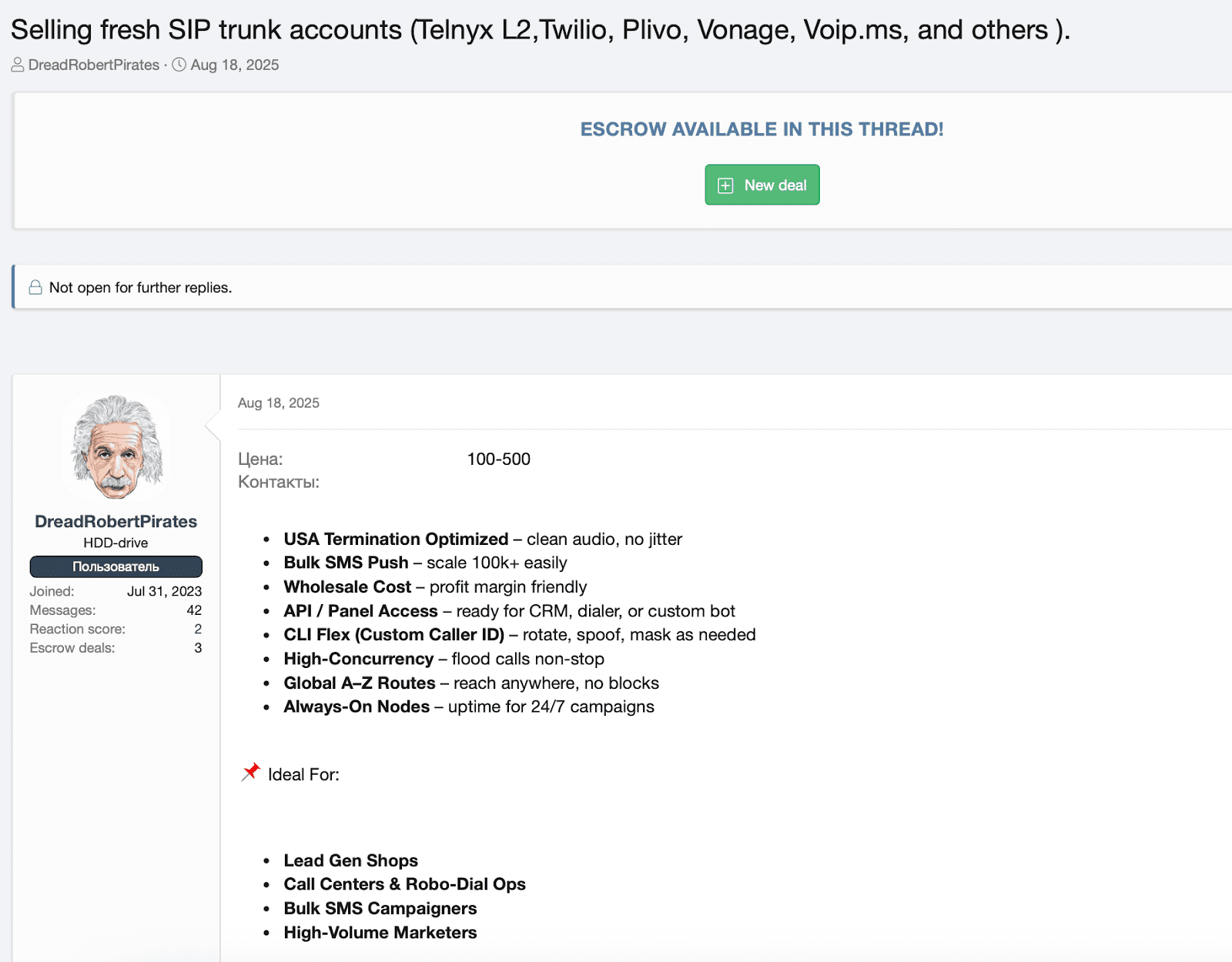

Abusing VoIP/SIP and Telecom Infrastructure

More skilled cybercriminals will exploit telecommunications systems to send their messages. One approach is abusing VoIP providers or SIP trunks - for example, purchasing a SIP trunk (internet telephony service) with cryptocurrency to stay anonymous and then using it to send SMS via the connected gateway. This kind of abuse of telecom infrastructure, whether it’s a cloud API like Plivo or an ISP’s router, gives attackers an illicit SMS gateway that is much harder to attribute.

Figure 6: A cybercrime forum listing selling SIP/VoIP trunks for bulk SMS sending.

We also see some groups using SIM farms and GSM modems (racks of SIM cards) or even rogue cell towers (“SMS blasters”) to broadcast texts in a region. The downside for attackers is these methods require more effort and hardware; the upside is that they can sometimes bypass carrier filtering by injecting messages directly into networks. The common theme is living off the land: hacking or misusing existing telecom services to send massive SMS volumes while evading detection.

Victim Perspective - What the Target Sees

From the recipient’s point of view, a smishing attack arrives as an unexpected text message on their phone, one that appears legitimate at first glance. Understanding the victim’s perspective is useful because attackers carefully write the content and presentation to maximize the chances someone will be tricked. Let’s break down what these messages look like:

Message Content and Tactics

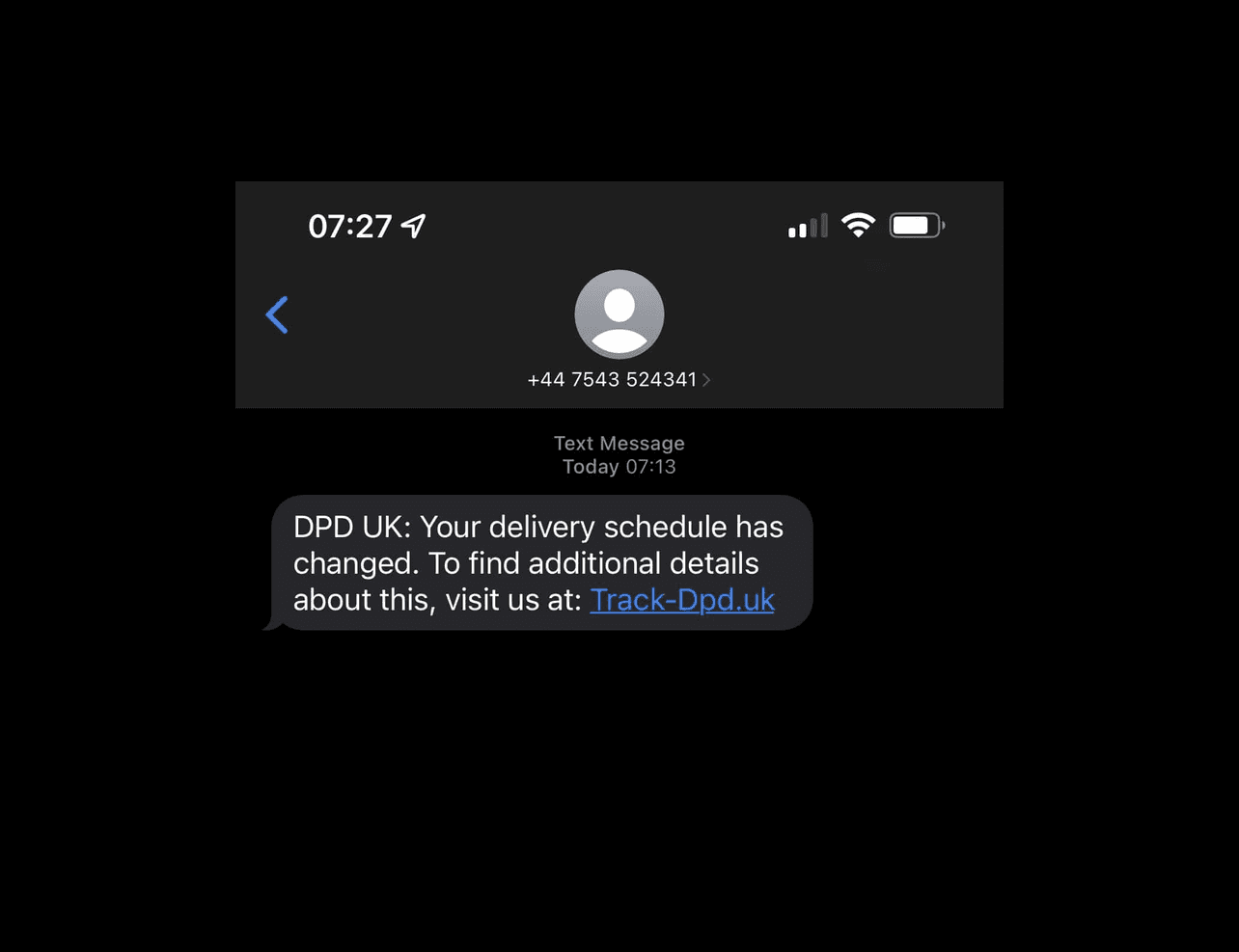

The SMS usually tries to induce panic or curiosity. Common themes include security alerts (“Bank Notice: Suspicious login, your account is locked!”), delivery problems (“Your package is delayed, update info here:”), prize winnings, or urgent account notices. The text is almost always brief and urgent in tone, often explicitly instructing the user to click a link or call a number right away. The attackers impersonate trusted senders - banks, online services, government agencies, to lower the victim’s guard.

Figure 7: DPD delivery smish example pushing a malicious link.

In many cases, the SMS includes a link (often obfuscated) that leads to a phishing site made to look like a real login page, where victims enter credentials or personal data. Other times, the message may urge the target to call a phone number that reaches an automated voice system (this blend of smishing and voice phishing is sometimes called vishing, where the text sets up the victim to divulge information via call). The unifying factor is a sense of urgency. Cybercriminals want the recipient to act impulsively, and to share sensitive information, before thinking it through.

Spoofed Sender ID

Technically, one of the most convincing aspects from the victim’s view is that the sender appears legitimate. Attackers manipulate the sender information so that the SMS shows an ID or phone number that matches the real institution they’re impersonating. On mobile networks, businesses often send texts using a name (e.g. “ChaseBank” or “HMRC”) instead of a number, and attackers exploit this feature.

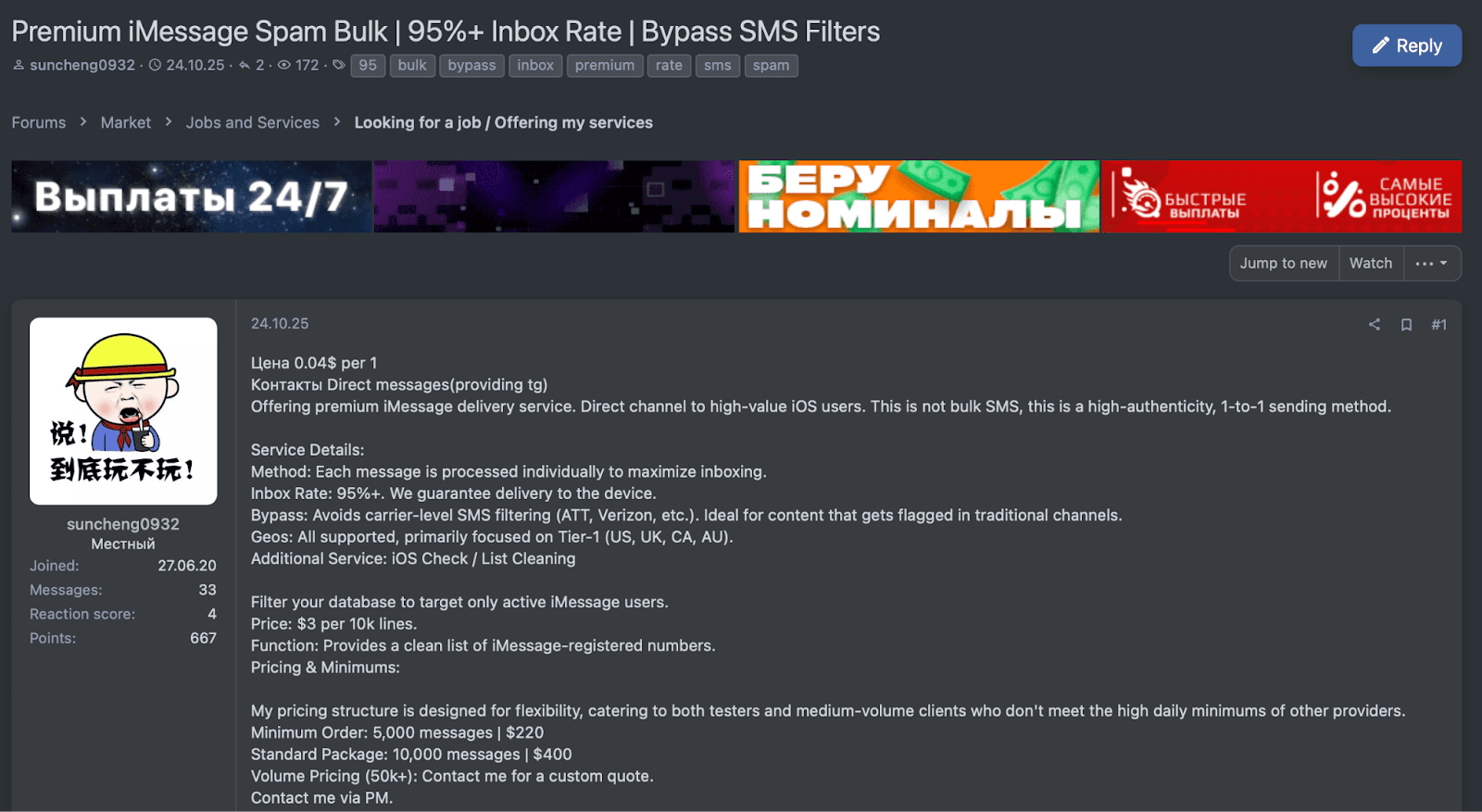

Figure 8: iMessage spam service advertised for high deliverability.

A scam text can be made to look like it came from “Apple” or a local-looking number, etc., rather than a random unknown number. Because carriers do not strictly verify that someone sending an SMS as “YourBank” is actually authorized to use that name, the scam SMS can slip right into the same message thread as genuine texts from the real entity.

The Message Look and Feel

Aside from the sender name, attackers try to make the message body look legitimate. Often the texts use fragments of personal information or context (perhaps the target’s name, or mentioning a bank they use) gleaned from those data breaches or broker lists. A lot of fraudulent SMS include bad URLs - e.g. a misspelled bank domain or a shortlink. A user might notice the URL is not quite right (e.g. mybank-secure-login.com instead of the bank’s official site), but it’s not always obvious.

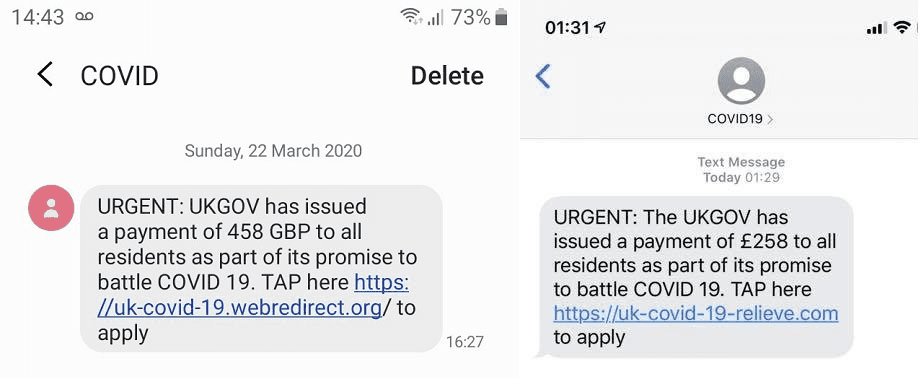

Figure 9: COVID-themed smishing examples designed to trigger urgency.

Some messages even reference recent events (like “COVID relief” or a local bank promotion) to appear timely. It’s worth noting that while most smishing aims for a clickable link, some campaigns do forego links and directly solicit information via reply text or phone call. However, the inclusion of a link to a phishing site is extremely common because it automates the theft of credentials or installs malware quickly.

Business Impact - Why SMS 2FA Is Under Siege

Beyond individual victims, smishing poses an acute threat to organizations that rely on SMS-based two-factor authentication.

Attackers can now deploy adversary-in-the-middle (AitM) phishing kits that intercept and relay credentials in real time. When a victim enters their password on a phishing site, the attacker's proxy forwards it instantly to the legitimate service, triggering an SMS 2FA code. The victim receives the genuine code, enters it on the phishing site, and the attacker relays it to complete authentication, all within the code's 30- to 60-second validity window.

Business-targeted campaigns are particularly problematic here because attackers conduct extensive reconnaissance to create highly specific pretexts. They compile employee contact lists from data breaches, LinkedIn scraping, and data brokers, then map out organizational structures and technology stacks.

With this intelligence, they tailor attacks to specific departments. Finance teams might receive texts appearing to come from expense management systems like Concur or Expensify. Engineering teams see fake alerts that look like they're from GitHub or GitLab. These campaigns achieve higher conversion rates than generic smishing because they reference the actual tools employees use every day.

Conclusion and Next Steps

As we’ve explored above, smishing campaigns are a blend of data compromise and social engineering. They continue to bypass technical defenses by targeting the human link. Each stage of the smishing kill-chain, from underground phone number markets to spoofing tools and localization tactics, leaves signals that security teams can look out for. This is where threat intelligence and specialized mobile security solutions come into play.

iVerify equips security teams with the tools and intelligence to spot smishing risks before they impact users. Our mobile threat intelligence platform keeps track of emerging smishing infrastructure, from newly registered phishing domains to unusual SMS sender patterns, giving defenders early warning of campaigns targeting their sector.

More Blogs

Get Our Latest Blog Posts Delivered Straight to Your Inbox

Subscribe to our blog to receive the latest research and industry trends delivered straight to your inbox. Our blog content covers sophisticated mobile threats, unpatched vulnerabilities, smishing, and the latest industry news to keep you informed and secure.